I used to get flashbacks every August.

The aching sadness would start to swallow me on the anniversary of the Aug. 2, 1985 crash of Delta Airlines Flight 191 in Dallas, followed by another collective sob on the anniversary of the Aug. 16, 1987 crash of Phoenix-bound Northwest Airlines Flight 255 in Detroit.

As a young reporter, I covered those crashes with both sides of my brain and 110 percent of my heart.

In the months after the Delta crash in Dallas, I and a team of two dozen reporters and editors at the late, great Dallas Times Herald produced a series on aviation safety that was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in Public Service Journalism.

Two months later, I quit my job in Dallas and moved to Phoenix to marry an editor, the love of my life, Bill Waldrop.

Bill directed breaking news coverage as Criminal Justice Editor at the Arizona Republic, a big, metro daily paper that wasn’t particularly interested in hiring me. So I went to work for Max Jennings at the Mesa Tribune, a paper that was still small enough to be nimble and scrappy.

Bill and I were watching the television news shortly after 5 p.m. Sunday Aug. 16, 1987 when the crawl went across the bottom of the television screen: “A Phoenix-bound jet has crashed on takeoff in Detroit.”

Back then, we only had one land-line telephone in the house, so there was a bit of an arm-wrestle about which of us would call their news desk first and say, “I’m on my way in to cover it.”

He won, and was out the door in a flash, speeding downtown in his Datsun 260 Z.

Not long after, I was off to Phoenix’ Sky Harbor Airport to interview people who were waiting for friends and family to arrive from Detroit.

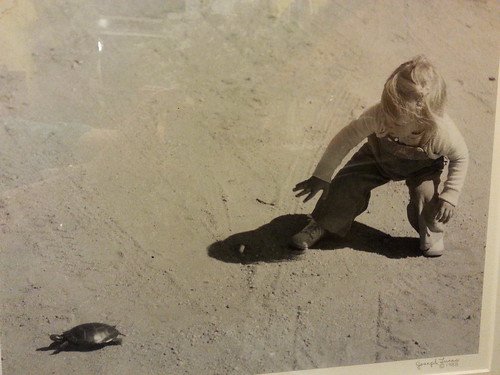

My dear photojournalist collaborator and friend, Gary O’Brien, still has a photo in his portfolio from inside the airport that night. I’m squatting down with other people, trying to comfort a woman who collapsed, overcome to learn her family member had missed the flight. He lived.

Photo by Gary O’Brien

Of the 157 people who boarded the plane, only one survived, a 4-year-old child named Cecilia Chichan.

I filed a story for the Mesa Tribune that evening, and also filed something for my friends at papers in Dallas and Detroit to include in their stories for the morning.

Then, after I cajoled him on the phone for a long while that night, Mesa Trib Managing Editor Sandy Schwartz relented, and Gary and I boarded a 2 a.m. flight from Phoenix to Detroit. The Mesa Trib had never done anything like quite like that before, and it certainly wasn’t in the budget.

When Gary and I landed after daylight, Andy Hall, a reporter working for my husband, was already on the ground in Detroit.

Gary and I went straight to the crash scene.

The aviation safety series in Dallas taught me more than I ever wanted to know about the fragile mechanics of JT8D Pratt & Whitney jet engines and the deadly vagaries of weather and wind shear.

As a 10-year-old kid, I learned the basics of aerodynamics by flying radio control planes with my Dad. I was his mechanic.

But the human factor arches over all.

For the “first responders” — EMS, Fire Department, local police and sheriff’s deputies — there is nothing more horrifying and debilitating than doing absolutely everything right – by the book – and not being able to change the outcome.

When big planes crash, people die. You can’t save them, no matter how hard you try.

When I met Wayne County Sheriff’s Lt. Norm Colstrand at the perimeter of the crash scene, I asked how he was holding up. I wanted the real answer, not just a polite response.

Colstrand was a burly, veteran cop. But he was overwhelmed with a primal pain.

We agreed that I would come back, long after dark, to see what he was guarding. He needed to share his pain with the world.

Having entered the game, the Mesa Trib doubled down and sent a gifted young writer, Doug MacEachern, to join the ground team in Detroit.

Doug mercifully agreed to connect with my husband and pick up my sneakers before leaving Phoenix. I’d been in heels since Sunday evening.

When he delivered them, I found a note from my husband tucked inside one sneak: “I love you – now kick ass!”

I wore those sneaks that night on a tour of the still smoldering crash scene.

Very fortunately for me, Gary and Doug were there. Doug tells the story here, better than I ever could.

I remember picking up the page, thinking deeply about the person who owned the book it came from, and tucking it away. It lives in my home in a file labelled, “Detroit Page.” It has seen daylight fewer than six times in 25 years.

From the start, I knew the plane did not crash itself. Even back then, passenger jets were designed to take off and fly with just one engine.

Sort of like in “rock, paper, scissors,” the human factor can overrule mechanics.

And so it had in Detroit, I learned through whispered hallway conversations with pilots and investigators.

Humans in the cockpit failed to extend the flaps on takeoff. Without that lift, the plane crashed.

To the relief of the reporters working for my husband, I finally left Detroit and flew home to Phoenix. He let them come home too.

The amazing experience in Dallas provided a template for the components that needed to be in the Sunday story.

The People.

The Plane.

The Crash.

Dave Becker, Scott Bordow, Ric Clarke, Jeffrey Crane, David Downey, Chris Feola, Earl Golz. Andrea Han, Eileen Myers, Robert Perez, Bill Roberts, Jeremy Stockfisch, Ed Taylor, Ben Winton, Rick Wiley, Dough MacEachern, Gary O’Brien and I provided the facts.

Then Doug wove the words together in just the right way, describing the purple bow her grandma tied around Cecelia’s waist that morning and the yellow blankets we saw that dark night tucked around victims on the ground.

After a long time, the ghosts went into remission.

But this August, they came out to mark 25 years.

And Norm Colstrand’s words echo in my brain:

“You hear about the plane crashing into Mt. Fuji and that 520 people got blown across the side of a mountain, and you say to yourself, ‘Boy, that’s a shame,’ and then you go about your business.

Or your hear about a plane crash in the Canary Islands and that 582 people were killed. You shake your head, and you go on with your life.

“But this time, we can’t just go about our business.

“This time, death in its massiveness came to roost here.”

Kelly and Portia are home, awaiting our return.

Kelly and Portia are home, awaiting our return.